I will never forget the day my fifth-grade teacher projected an essay I had written in front of the whole class as an example of C-level writing. Like vultures extracting the last of stale flesh worth dissecting, he picked apart the lines that I had pieced together, leaving only the ribs of a carcass I was no longer proud of.

Granted, it wasn’t my brightest work– I couldn’t even tell you what the paper was on, thankfully, as it was over twelve years ago. What I do remember is that that moment confirmed to me at the ripe age of ten a simple truth: I was not a writer.

Growing up in an immigrant household, English was not my first language. My parents didn’t learn the alphabet until high school. They spoke to me in Chinese, sometimes tossing an English word between the strings of Mandarin– it always sat awkwardly on their tongues. Every evening, they fed me a porridge of broken English and a fluid mother tongue. That’s all I ever knew until I tasted the American education system.

Yet somehow, the library was always my sanctuary. Maybe it was the free stack of coloring pages and oversized picture books that drew me in, but the stories were what kept me returning. My obsession with Junie B. Jones turned into a love for Roald Dahl, and before I knew it, the books I borrowed held fewer pictures and more words. I drank up the pages like honey.

In eighth grade, Lois Lowry’s The Giver was part of our curriculum. At the end of the year, it was tradition for my teacher to play the role of the Chief Elder and assign jobs to each student: ‘doctor’, ‘caretaker’, ‘fish hatchery attendant’, etc. (no one wanted to be a birthmother). When she called my name, I proceeded to the front of the class.

Her exact words blur in my memory, but something about reading and writing being my strengths earned me my role: lawyer. I think that it subconsciously lodged itself deep inside me. After all, what other respectable career could grow from a love of literature?

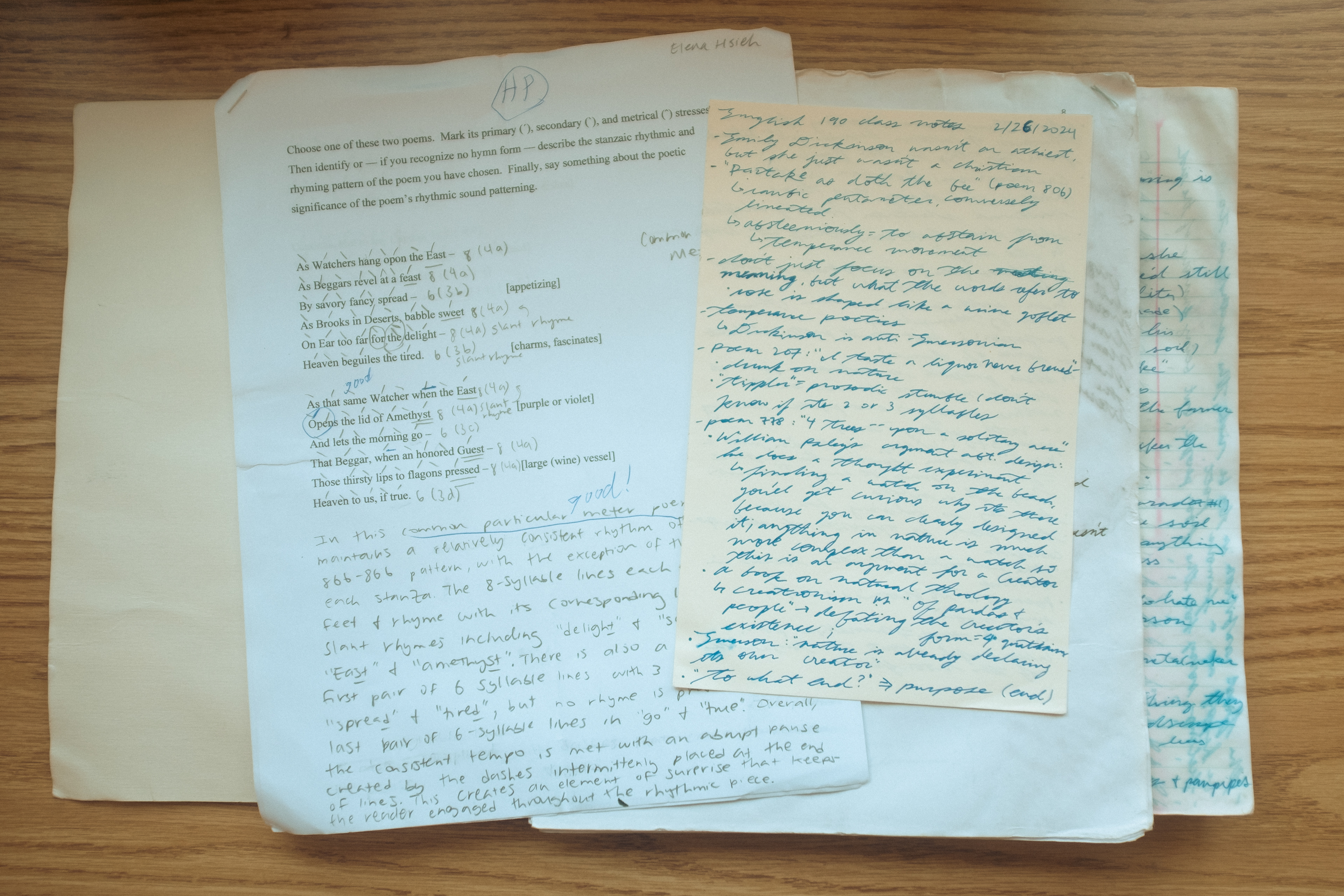

The first English class I took in university (45A, I do not miss you one bit) changed everything. One of the texts we studied was John Milton’s Paradise Lost, a 17th-century epic poem. There was nothing epic about it at all.

Up until this point, the books I had read throughout high school made sense. The Great Gatsby, Catcher in the Rye, The Odyssey– they all had well-defined characters and a clear through-line. I did not have to tread through heavy waters to catch a symbolic raft or a far-reaching theme.

Paradise Lost, however, was a different beast. Five hundred dense pages of metrical lines and archaic language morphed into something almost foreign. Getting beyond the form was one feat; combing through the content was another. I remember sitting in lecture wading through waist-high wetlands, trying to grasp the subtle nuances I had skimmed over in my initial read-through.

It was then that I realized how shallow I had been reading– passive absorption, and not active comprehension. I could no longer take the highway when it came to reading. My mind was cultivating new roads for neural networks, paving uncharted terrains in hopes of picking up what authors centuries before me put down.

After poring through endless readings in my literary career, I began to see a pattern: the reader’s task is to turn the finite words on a page into the infinite: thoughts and ideas that stretch beyond it. The writer’s task is the inverse: to transform the infinite, a tangled web of impressions, into the finite: an article, a book, a body of work. The brain is the hinge between the two, producing limitless ideas meant to be shared beyond the confines of the skull.

Understanding this dynamic makes it clear that good writing doesn’t come solely from distilling concepts into digestible lines of text, but from a mind capable of shaping, interpreting, and articulating them in the first place.

To be a good writer, you have to write. Just like cooking one dish won’t make you a chef, writing literary analysis and research papers in an academic setting can only fine-tune your writing skills so far. So, what actually makes a good writer? Is it the ability to thread words together symphonically, like a composer blending the perfect balance of tonalities to strike a chord in the audience? Is it the precision of editing, paring ideas down until nothing unnecessary remains? Or is it something much more elusive– an essence that a reader can’t quite name but inevitably feels?

While I can’t distill such an abstract question into an all-encompassing answer, the great writers I look up to share three core strengths: thinking, observing, and feeling.

The first strength is depth of thought. A good thinker doesn’t rely on rote memorization or blind acceptance; they interrogate ideas from multiple angles, wrestle with unconventional interpretations, and catch the subtleties tucked in the heart of their own argument.

The second is intentional observation– how someone sees and perceives the world. The ability to slow down and let life seep into their lived experience forms the bedrock of inspiration. These collected noticings evolve into questions, and when left to simmer with curiosity, they crystallize into layered perspectives that make writing breathe.

The last is empathy. Someone who feels deeply can understand stories beyond their own and weave universality into their work. Their writing carries authenticity because their emotional experience is too real to be reduced to a façade; they can capture and transcribe the pulse of emotion onto the page.

Together, these strengths form the interior scaffolding of good writing far beyond grammar or technique.

Anyone can write. Fifth graders can write. Heck, even AI can write. But to be a good writer requires a more substantive body of inner work, an intuition sharpened by logical and emotional processing.

Back when I was in university, people asked, “So… what do English majors even do?” The short answer is predictable: a lot of reading and writing—wash, rinse, repeat. So I can imagine why the title of this piece might puzzle you. If writing is half of what we do, how could studying English not make me a good writer?

Because that would be a shallow reading (pun intended). Writing is only the surface layer of what we do. Beneath it lives the real work: observing, analyzing, questioning, understanding, imagining, creating. In classes with our entire grade hung on three papers, we weren’t being evaluated solely on the quality of our prose but on how clearly we thought, how sharply we noticed, and how deeply we felt.

And a small piece of me still wants to believe those are the very qualities that AI can’t replicate, despite its growing ubiquity. There is something distinctly human about great writing; It takes soul to not sound artificial.

College catalyzed that process for me. It was four years of simmering in a crockpot of perspectives from peers and professors whose life experiences varied from mine. Being surrounded by an abundance of brilliant minds didn’t magically make me a good writer, but it did make my understanding of the world more textured.

I’m not saying you need to attend college or even study English to be a good writer; many of the writers I admire never set foot in an academic institution. And plenty of college-educated people outsource emails and other written deliverables to AI because they’d rather not expend brain power on grammar (honestly understandable).

But this isn’t an anti-academic take. It’s simply a recognition that writing well isn’t the same as doing well in academic writing. Instructor feedback and timed on-demands can only take you so far, and the formulaic nature of academic prose can even drown out your real voice. What college offers, instead, is the environment—the conversations, the perspectives, the intellectual friction—that deepens the mind behind the writing.

So, no, majoring in English didn’t teach me how to write. It taught me how to inhabit my mind more deeply, to move through the world with sharper eyes, to feel with a wider heart—and somehow, all that inner work nudged me into becoming a better writer anyway.

Because writing isn’t just an academic skill; it’s a way of living. Every thought and emotion I pour onto the page has to come from somewhere, and that somewhere is the messy, unglamorous, wonderfully complicated business of being alive.

And twelve years later, I’ve learned one more simple truth: I am a writer. And with a little more thinking, observing, and living, I just might grow into a great one.